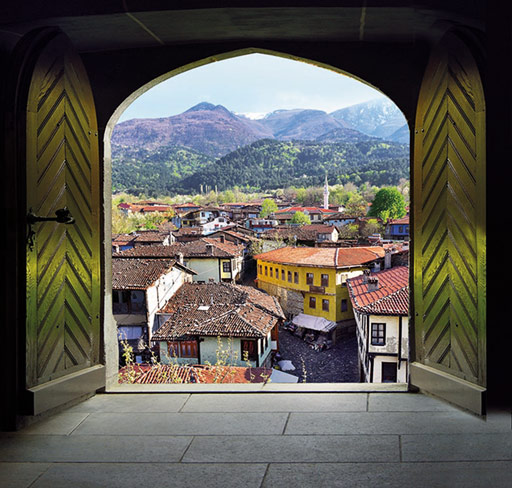

Odundan kömür, kömürden kara

Coal from wood, blacker than coal

Odundan kömür, kömürden kara / Coal from wood, blacker than coal

Ateşe yol veren o. Demire yaşam şansı veren, eriyen ve eriten. Sıcak bir hikâye bu. Tek başına yanamayan, dönüşen.

It is what gives way to fire. What gives life to iron, melting itself while making it melt. This is a hot story. Not able to burn by itself but gets transformed.

Fotoğraflar: Mustafa Serdar Taşkın

Hikayelerine vesile olan kişiler her geçen gün azalıyor. Doğalgaz şehir şehir gezdikçe onlar daha da azalıyor. Kim mi? Odundan odun kömürü yapan insanlar nam-ı diğer torakçılar. Odun kömürü alırken hangimizin aklına geliyor bu kömürlerin nasıl ortaya çıktığı?

The number of people who contribute to their stories is dwindling with each passing day. Their numbers are in decline as natural gas moves from city to city. You may be asking who they are. Those who make charcoal from wood, also known as torakçı. Who among us was thinking how charcoal is produced when we used to purchase it?

Örslerde dövülen demiri, tunç yontulara kavuşturan ateşin kaynağı bu insanlar. Tek başına yandığında yeterli ısı oluşturamayan odunun yerini odun kömürünün almasıyla bakır ve kalay eritilerek tunca dönüştürülmüş, demir işlenebilmiş, pek çok el aletlerinin yapımı bu sayede mümkün olabilmişti.

They are the source of the fire that unites iron forged on anvils with bronze hammers. When charcoal replaced wood which could not provide sufficient heat by itself, copper and tin were molten thus forming bronze; iron could be processed thereby producing many of the tools that we use.

Diyelim ki mangallı bir piknik yapmak istiyorsunuz. Etinizi en kıvamlı pişirecek, ızgaranızı en dengeli ısıtacak kömürdür odun kömürü. Ama mangal yakmaktan çok daha zor, çok daha zahmetli bir süreç ile yapılıyorlar.

Let us say that you wish to go to a barbecue picnic. Charcoal is the type of coal that will cook your meat in the most consistent manner. But they are produced as a result of a process that is much more difficult and arduous than making barbecue.

Harlanmış birçok tarihi ateşte sonsuz bir değişimin anavatanı olan Anadolu’da halen üretilen odun kömürü neredeyse ilk yapıldığı tarihten bu yana aynı yöntemlerle yapılabiliyor. Günümüzde kullanım alanları ve tüketimi giderek azalmaya başlasa da değerinden bir şey kaybetmiyor.

Charcoal is still being produced using the same historical methods in Anatolia, home to infinite changes over a well flared fire. They have lost nothing of their value even if their areas of consumption are in decline.

Torluk ve Torakçılar

“Orman bölge müdürlükleri her sene ormanlık alanlarda köylülerin kesim yapılabileceği bölgeleri belirliyor. Köy muhtarları da hane ve hane halkı sayısına göre kesim bölgelerini paylaştırıyor. Bu kesim alanlarına “makta” deniyor. Eskiden tümüyle kesilen ağaçların, son yıllarda seyreltme yöntemiyle kesilmesine izin veriliyor. Ormanların daha sağlıklı büyüyebilmesi için uygulanan bu yöntem, bölge halkı için daha az odun anlamına geliyor, temel geçim kaynakları giderek daralıyor. Birçok aile bu yüzden odun kömürü üreticiliğini yavaş yavaş bırakmaya hazırlanıyor.

Torluk and Torakçı

“Regional directorates of forestry determine the forest locations every year where villagers can cut down trees. The village headmen distribute these locations to the households according to the number of people in the household. These locations are known as “makta”. The trees that were allowed to be cut down completely in the past can now be cut down only by thinning method. This method that is applied to ensure that the forests grow stronger means less wood for the local public resulting in a decrease of their fundamental source of income. That is why; many families are preparing to stop charcoal production.

Çok iyi kömürleştiği ve sert olduğu için kömür yapımında çoğunlukla meşe ağacı tercih ediliyor ve bu kömürler mangal kömürü olarak satılıyor. Gökçeağaç’tan imal edilen odun kömürü ise nargilelerde kullanılıyor.

Oak tree is preferred the most for coal making since it has the best charring quality and also due to its hardness and the coal that is produced is sold as barbecue coal. Charcoal produced from willow tree is used mostly in water pipes.

Odun kömürü üretimi için kurulan, üzeri toprakla örtülü ocağa “torluk” adı veriliyor. Torluklar kurulurken, ortasından 30 cm mesafede olmak üzere 3-4 sırık dikiliyor ve torluktan daha yüksek olan bu sırıklar, yanma aşamasında baca görevi görüyor. Baca içerisine kolayca yanabilen talaş, yonga, çalı çırpı dolduruluyor. Baca etrafınaysa, havalanmayı sağlamak amacıyla, ince çaplı veya yarılmış kuru haldeki odunlar altlık olarak yerleştiriliyor. Daha sonra kömür haline getirilecek odunlar çepeçevre diklemesine istif ediliyor. Çevreye doğru gidildikçe odunların çapı giderek inceliyor. Kömürleştirme esnasında havayla doğrudan teması kesmek üzere istifin üzeri bir örtüyle kaplanıyor. Bu örtü bazen orman içinden toplanan gazel denilen kurumuş yapraklardan ya da samandan yapılıyor. Ardından, ıslatılmış kömür tozu ve topraktan oluşan ikinci bir örtü ile hava almayacak şekilde sıvanıyor. İç kısımda, torluğun ilk kuruluş aşamasında hazırlanan tutuşturma kanalından yararlanarak baca içerisindeki talaş, yonga, çalı-çırpı gibi tutuşturucu maddeler üstten ve alttan yakılıyor.

The oven covered with soil that is built for charcoal production is called “torluk”. A total of 3-4 sticks are erected at a distance of 30 cm from the center when building a torluk and these sticks that are taller than the torluk serve as a chimney. The chimney is filled with sawdust, chippings and brushwood that can burn easily. The chimney is surrounded with thin or cracked dry woods as a base plate. Afterwards, the woods that will be transformed into coal are stacked up perpendicularly. The diameter of the woods decreases as we move outwards. The stack is covered with a cloth during coalification in order to stop direct contact with air. This cloth is called gazel and is generally made using dried leaves or hay from the forest. It is then coated with a second layer made of wetted coal dust and soil. The sawdust, chippings and brushwood are burnt from the bottom and the top using the flaring channel that was built while erecting the torluk.

Torluğun yakma işlemine sabahın erken saatlerinde ve mutlaka rüzgârsız bir havada başlanıyor. Torluk içerisindeki ateş, üstten yanlara ve aşağıya doğru yelpaze biçiminde yayılıyor. Ateşin ilerlemesini kontrol altında tutmak için torluğun toprak örtüsü üst kısımlarından başlanarak deliniyor. Bu deliklerden ilk önce su buharı çıkıyor, daha sonra ise sarı renkte bir duman yükseliyor. En sonunda karbon monoksitten ibaret mavi renk meydana geliyor ve bu kömürleşmede sona yaklaşılmış olduğunu gösteriyor. Bundan sonra delikler tıkanıyor. Torluğun dip kısmına açılan deliklerden beyaz duman çıktığı görüldüğü zaman kömürleşmenin sona erdiği anlaşılıyor. Ve torluk birkaç gün soğumaya bırakılıyor. Soğuyan torluk açılınca ilk olarak “elleme” adı verilen, bütünlüğü bozulmamış odun kömürleri daha değerli oldukları için diğerlerinden ayrılıp, istifleniyor. Odun kömürlerinin çıkarma işlemi bittiğinde çoğu zaman en alt kısımlarda yarı yanmış odun parçaları kalıyor. Bunlara da “marsık” deniyor. En son işlem bittikten sonra bu yanmamış olan marsıklar toplanıyor, daha önce yapılandan daha küçük bir torluk kuyusu oluşturulup ve tekrar ateşe veriliyor. Buradan çıkan odun kömürünü köylüler genellikle kendi ihtiyaçları için kullanıyor.” (Kaynak: Medeniyetin Ateşi Odun Kömürü, Atilla Erdoğan)

The torluk is kindled during the wee hours of the morning in calm weather. The fire inside the torluk spreads out as a fan from the top towards the bottom and the sides. The soil layer of the torluk is pierced starting from the upper sides in order to control the spreading of the fire. At first, water vapor comes out of these holes, afterwards a yellowish fume emerges. And finally a blue color is formed due to carbon monoxide which indicates that the end of the coalification process is near. Afterwards these holes are closed. Coalification ends when white smoke comes out from the holes at the bottom of the torluk. And the torluk is left to cool for a few days. When the cooled torluk is opened, the valuable and intact coal known as “elleme” are separated from the others and stacked up. Semi-burned wood pieces generally remain at the bottom when all charcoal is removed. These are called “marsık”. These unburned marsık pieces are collected at last after the process is over, a smaller torluk well is formed and they are burnt again. The resulting coal is generally used by the villagers for their own needs.” (Reference: Fire of Civilization: Charcoal, Atilla Erdoğan).