Onlar gitti, zanaatları kaldı Bursa’da

Rabia Deniz yazıları

Onlar gitti, zanaatları kaldı Bursa’da

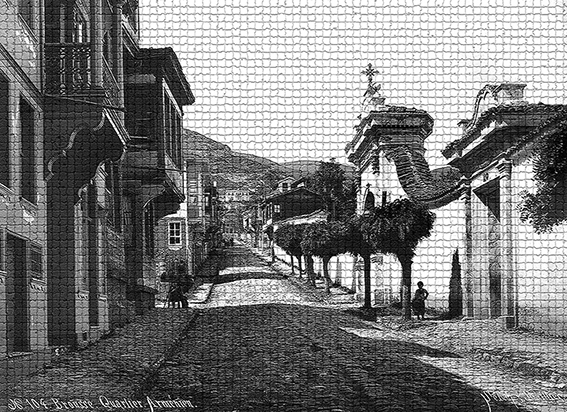

Bursa sanayisinin hafızalarından Ergun Kağıtçıbaşı, iktisatçı Enis Yaşar’la birlikte, Bursa’nın Ekonomi Tarihi adlı kitabın ikinci cildine imza attı. Bursa’nın 1900’den 1960’a kadar olan, ekonomik ve sosyolojik tarihçesinin özetlendiği kitap, Bursa’daki tüm ekonomik varlıkların yabancıların elinde olduğuna dair önemli bilgiler veriyor. 1587- 1589 yılları arasında, Osmanlı’yı ziyaret eden Reinhold Lubenau, 1588’de Mudanya yoluyla Bursa’ya geldiğinde gördüklerini şu şekilde özetliyor: “5 Temmuz sabahı Mudanya Beldesi’ne ulaştık. Kentte Türkler, Hristiyanlar ve Yahudiler yaşıyor ve gümrük vergisini tahsil etme işi Yahudilerin elindedir. Mudanya Bursa’nın iskelesi ve Konstantinapolis’ten gelen yolcuların uğrak iskelesidir.” 20. yüzyılın başlarındaki Bursa’nın Şark Ticaret Yıllıkları (İndicateur Constantino- politain) Raphael Cisarvati ve bir arkadaşı tarafından Türkçe ve Fransızca olarak 1868 yılında yayınlanıyor. Yayın Türkçe’ye çevrilip Ermeni harfleriyle Tarif’i der El Saadet adıyla 1870 yılında tekrar yayınlanıyor. Bu yıllıklar, yabancı nüfusun yoğunluğunun Bursa’da azımsanmayacak derecede fazla olduğunu gösteriyor.

1831 yılında yapılan sayımda Bursa, Anadolu eyaletinin Hüdavendigar Sancağı’na bağlıyken, 1878 ve 1994 yıllarındaki nüfus artışı göçlerle gelen vatandaşlarla arttığı, 1870-1900 yılların arasında ise en az 1 milyon kişinin Anadolu’ya göç ettiği belirtiliyor. Gelen göçmenlerin yerleştirilmesi İstanbul’da kurulu Muhacirun komisyonu tarafından vilayetlerdeki temsilcileri kanalıyla yapılmış ve bundan sonra Bursa’ya olan göçler Balkan Harbi ve mübadele nedeniyle ortaya çıkmıştı. 1902 yılında Bursa Sancağı’nın nüfusu 282 bin 870 kişiyken nüfusun 60 bini Müslüman, 14 bin 350’si Rum, 13 bini Ermeni, 2 bin 500’ü Yahudi vatandaşlardan oluşuyordu. Bursa’da kazanıp Bursa’ya kazandıran tüccar ve sanayiciler arasında Ermeni, Yahudi, Rum nüfusu geniş yer alıyor. İpek ticareti yapanından tutun sigortacı, avukat, komisyoncu, mücevherat, sarraf, bakırcı, derici, ayakkabıcı, kuaför, perdeci, dişçiye kadar pek çok sektörde Ermenilerin, Yahudilerin ve Rumların izleri vardı. Hatta bu kente özgü Bursa havlusunu bile Ermeni İplikçiyan, Derhoronyan ve Morukyan’dan alanlar vardı. Kentteki eczacılar Apostolidis, Dalabiras, Mihalopulos da Bursa’nın ekonomisine katkı sağlıyordu.

Rumlar kayıtlara göre Ahmet Bey, Attar Hüseyin, Bazar-ı Maki, Bucak, Bulgarlar, Demirkapı, Hacı Yakup Hoca, Yahşibey mahallelerinde otururken, Ermeniler bu tarihlerde Setbaşı ve Yeşil civarında, Hisar Bölgesi’nde yaşıyordu. 93 Harbi diye anılan 1877-78 Osmanlı Rus Savaşı sonrasında imparatorluğun bozgun göçleri başlamış, Balkan Savaşı sonrasında devam etmiş Cumhuriyet Dönemi’nde Büyük Mübadele işlemiyle göçün son durağı olmuştu. 93 savaşı sonrasında balkanlarda 1 milyon Türk göçe zorlanmıştı.

Bursa’daki göç hareketlerinden bahsederken Ermeni Tehciri’ne önemli yer vermek gerekiyor. Orhan Bey’in devrinde, Bursa başkent olduktan sonra, Kütahya’daki Ermeniler Bursa’ya getirildi. Ermenilerin önemli bir bölümü 1915 yılından sonra bir daha bu topraklara gelmedi. Çoğu da toprağıyla birlikte en güzel anılarını bıraktı Bursa’da… Yüzyıl önce İznik’te yaşayan Demirci Ustası Nubar’ın oğlu Hariazad’ın hikayesini kaleme alan Güney Özkılınç’ın “Tekerlekli Karyola” öyküsünü paylaşmak istiyorum bu satırlarda…

Tekerlekli Karyola…

Yüzyıl sonra oda kapısının eskimiş sesiyle içeri girdim. Mustafaların evi. Köşedeki karyolaya oturdum. Tahta çeyiz sandığı, beyaz tüller giydirilmiş kestane ağacından pencereler, duvarda sarıya çalan efendi fotoğraflar… Henüz biten yağmur ıslak topraklar üzerinde dinlenirken, gülümsemeye başlayan güneş köyün kurulduğu tepeden göle doğru uzanan çiçek denizinin üzerinden genişçe bir vadiyi andıran koridor açmıştı. Köye kıvrılan yer yer taşlarla kaplı toprak yolun her iki yanında; yemyeşil yaban otlarının arasına serpilmiş sarı sarı, mor mor çiçekler… Çiçekler içinde kırılgan yüzeylerinde siyah bulaşığı gelincikler kırmızı kırmızı… Bir tür çiçek patlaması…

Yağmur dinmişti dinmesine ama ağaçlara biriken su; daldan dala, yapraktan yaprağa geçiyor, doygunluğa ulaşır ulaşmaz kendini bilinçsiz hamlelerle aşağılara doğru bırakıyordu. Teni okşayan yel, toprağın taze kokusunu, çiçeklerin kokusuyla harmanlayıp savururken; yol kıyılarındaki çoban çeşmelerinden taşan sular kendi açtıkları yollardan uzayıp gidiyorlardı.

Zeynep, zeytinlikteki işini bitirdikten sonra eve gelir, annesinin ölümünden sonra yalnız kalan babasına akşam yemeği hazırlar ve soluğu kırlarda alırdı. Annesini kaybettiği gün de öyle yapmıştı. Çiçeklerin içinde çiçeklerden biri oluvermişti. İnce belli birinden beklenmeyecek irilikte dolgun memeleri, tülbendinin altından uzayıp inen saçları ve biriyle karşılaştığında etkisi altına alacağı anlamlı gözleri. Yine o çok sevdiği kırmızı gelinciklerin arasındaydı. Kanaviçelerinde papatyadan, nergise; ballıbabadan, sümbüle kadar birçok çiçeği işlerdi işlemesine ama gelinciğin yeri başkaydı…

Yakında, çocukluğunu paylaştığı Hairazad’la evlenecekti. Hairazad… Uzun boylu, demiri dövmekten kabarmış ve kaslaşmış göğsü; ince ruhlu, demirci ustası Nubar’ın oğlu… Birlikte yaşayacakları eve tüllerin, kanaviçelerin en güzelini götürmeliydi. Bedenleri, gelinciklerle bezeli mis kokulu nevresimlerin üzerinde değmeliydi birbirine. Yastıklarındaki çiçekler, tenlerinden akan terle sulanmalıydı. Hele o kayınbabası Nubar’ın bir aydır üzerinde çalıştığı, dört parçalı, ucundaki tekerlekler sayesinde odanın istenen yerine zahmetsizce sürüklenebilen karyola… Bir gün dibinde peri kızlarının yaşadığı maviye bakan; göllü pencere, diğer gün zeytin ve kirazlarla örtülü yeşile bakan; tepeli pencere…

O sabah havayı kaplayan pustan ne tepe ne de göl görünüyordu. Uykusunu üzerinden hâlâ atamayan Zeynep, esneye esneye köy meydanını gören pencereye yaklaştı. Belli belirsiz insan suretleri, tartışmalar, bağrışmalar… Kiraz ağacına her sabah tüneyip sonra uzun uzun şakıyan bülbülün sesi de duyulmamıştı. Telaş ve tedirginlik yeni doğan günü bitirmiş, gün yaşanmadan sanki gece oluvermişti.

Göl kıyısındaki köylerde uzun zamandır kulaktan kulağa yayılan söylentiye Mustafalar dahil kimse inanmıyordu. Bu topraklardan gidileceği gerçek miydi? Komşular, akrabalar; köpekler, kuşlar; zeytin ağaçları ve göl, göldeki balıklar nasıl gidecekti onlarla? Yaşanmamış gibi, bir hiç gibi… Adları farklı olsa da aynı oyunlarda terlemiş, aynı sokaklarda, çayırlarda kirlenmiş ve aynı çeşmelerden su içmişlerdi. Aynı çınar gölgesiydi yorgunluklarını alan. İki hafta süre verildi. Düğün üç hafta sonraydı. Giden son kafilenin çığlığı hala kulaklardaydı. Nereye gittikleri hiçbir zaman bilinmedi. Yaşayıp yaşamadıkları da… Oturduğum yerden kalkarak pencerenin önüne kadar yürüdüm. Nasıl olmuştu da fark edememiştim. Köşede pencereden uzakta işlemelerle süslü, kırmızı gelinciklerle işli kanaviçe örtü ve tekerlekli karyola…

They left but their crafts stayed in Bursa

Ergun Kağıtçıbaşı, a renowned figure for the industry of Bursa wrote the second volume of the Economic History of Bursa together with Enis Yaşar. This book that summarizes the economic and sociological history of Bursa during 1900 to 1960, provides important information regarding the fact that all economic entities in Bursa were controlled by foreigners. Reinhold Lubenau, who visited the Ottoman Empire during 1587 – 1589 summarizes what he saw in Bursa when he came there in 1588 from Mudanya as follows: “We reached the district of Mudanya on the morning of July 5th. There are Turks, Christians and Jews living in this city and the Jews control the customs tax collection. Mudanya as the pier of Bursa is the popular pier for passengers coming in from Constantinople.” The Orient Trade Yearbook of Bursa (İndicateur Constantino- politain) was published by Raphael Cisarvati and a friend of his in 1868 in Turkish and French. The book was translated into Turkish and was republished in 1870 as Tarif’i der El Saadet with Armenian letters. These yearbooks indicate that the foreign population in Bursa was quite high.

Whereas Bursa was part of the Hüdavendigar Sanjak of the Anatolian state during the census of 1831, it is put forth that population increased in 1878 and 1894 with increasing migration and that at least 1 million people migrated to Anatolia during 1870-1900. The settlement of the incoming immigrants was carried out by the Immigration commission established in Istanbul via representatives in districts after which migrations to Bursa took place due to the Balkan War and population exchange. The population of the Bursa Sanjak was 282 thousand 870 people in 1902 with 60 thousand Muslims, 14 thousand 350 Greeks, 13 thousand Armenians, 2 thousand 500 Jews. Armenian, Jew and Greek population was high among the merchants and industrialists who worked in and provided value to Bursa. There were traces of Armenians, Jews and Greeks in many sectors from sericulture to insurance, law, commission, jewelry, money exchange, coppersmiths, leather, shoemaking, hairdressers, curtain making, dentistry. Indeed, there were even those who purchased the Bursa towel that is unique to the city from Armenian Ermeni İplikçiyan, Derhoronyan and Morukyan. The pharmacists in the city Apostolidis, Dalabiras, Mihalopulos also contributed to the economy of Bursa.

According to records, the Greeks stayed at neighborhoods of Ahmet Bey, Attar Hüseyin, Bazar-ı Maki, Bucak, Bulgarlar, Demirkapı, Hacı Yakup Hoca, Yahşibey, whereas the Armenians lived around Setbaşı and Yeşil as well as the Hisar Region at this time. Following the Ottoman-Russian war during 1877-78 that was also known as the ’93 War, immigrations of the Empire started which continued after the Balkan War only to become the last stop of migration with the Great Population Exchange of the Republic Era. About 1 million Turks were forced to migration from the Balkans following the ‘93 war.

Armenian Deportation should be given significant importance when talking about the migration movements in Bursa. After Bursa became the capital during the reign of Orhan Bey, the Armenians in Kütahya were brought to Bursa. A significant portion of the Armenians never set foot on this land after 1915. Majority left their best memories behind in Bursa along with their homeland… I want to share with you the story by Güney Özkılınç entitled “Bedstead with Wheels” depicting the story of the Blacksmith Nubar’s son Hariazad who has lived in Iznik a century ago…

Bedstead with Wheels…

I entered a century later the with the sound the old door of the room. House of Mustafa’s family. I sat on the bed at the corner. Wooden dowry chest, chestnut windows draped in white gauze, yellowed photos on the walls… As the rain that just stopped rested on the wet soil, the smiling sun had opened up a corridor resembling a wide valley from the hill where the village was all the way to the lake over a sea of flowers. Yellow, purple flowers on both sides of the earth road leading up to the village covered here and there with stones amidst greenest of green weeds… Red poppies among the flowers… A kind of flower explosion…

The rain had ended, but the water that collected on the trees passed from branch to branch, leaf to leaf only to let itself go unknowingly. As the wind that caressed the skin mixed the fresh scent of the soil with those of the flowers; the waters that overflowed from the fountains along the roads spiraled away.

Zeynep would come home after finishing her chores at the olive grove, prepare dinner for her father who was left alone after her mother passed away and would then rush off to the prairie. That was what she had done on the day she lost her mother. She had become a flower among the flowers. Large breasts contrasting with her thin waist, hair flowing down from under her muslin and her meaningful eyes that can take hold of anyone who she comes across. She was again among those red poppies she admired so much. She used to engrave many flowers on her canvases from daisies to daffodils; from nettles to hyacinths but red poppies were special…

She would soon marry Hairazad with whom she shared her childhood. Hairazad… Son of Nubar, long, muscled chest from forging iron and of a fine spirit… She had to take the best canvases and gauzes to the house they would be living together in. Their bodies had to touch one another’s on fine scented bedclothes covered with red poppies. The flowers on the pillows had to be washed with their sweat. And that four-piece bedstead which could be rolled to anywhere in the room thanks to its wheels on which her father-in-law Nubar had been working on for a month… Windows one day overlooking the blue where once fairies lived and the next overlooking green hills covered with olives and cherries…

They could see neither the hill nor the lake on that morning because of the mist covering the air. Zeynep who was still sleepy approached the window overlooking the village square yawning. Faint silhouettes, cries, shouts… The sound of the nightingale that cried every morning had not been heard that morning. Haste and anxiety had finished off the day and it was as if night had fallen without the passing of the day.

No one including Mustafa and his family believed the rumors that spread around the villages around the lake for some time now. Was it true that they would have to leave these lands? How would the neighbors, relatives; dogs, birds, olive trees and the lake, the fishes in the lake go with them? As if none of them ever lived… They had sweated in the same games, on the same streets, on the same meadows and they had drank from the same fountains even if their names were different. It was the same shadow of the same plane tree they rested under. They were given two weeks time. The wedding was three weeks later. It was never known where they went to. Or whether they ever lived or not… I stood up from where I was seated and walked towards the window. How could I have not noticed. The wheeled bedstead at the corner, wrought with red poppies…