43

başlayan buz fabrikalarına

kadar en gözde mesleklerden

kabul edilmişti. Buzun önemi

büyüktü çünkü mutfaklarda

yemekleri özellikle sıcak

havalarda koruyabilmek,

sıcaktan etkilenip

bozulmamalarını sağlamak

neredeyse imkânsızdı.

Yiyeceklerin bozulmamaları

için buzun içinde saklanmaları

gerekiyordu. Buz aynı

zamanda çok sıcak geçen

mevsimlerde serinlemek için

de bir ihtiyaçtı. Bu ihtiyacın

karşılanması Uludağ’daki kar

ve buzların şehre getirilmesiyle

mümkündü. Buzcular ailesi,

padişahtan aldıkları izinle bu

yetkiye sahip olmuş, ortaya

çıkan “buz sektörü”nün tekeli

olmuşlardı. O dönemde

kar ve buzun değerini, hem

yalnızca bu iş için özel bir

izinle görevlendirilen ailenin

hem de sarayda yiyecek ve

içeceklerinin buz kalıplarının

içine koyulmasından sorumlu

olan “Karcıbaşı”nın varlığının

yanı sıra, 1768 yılında yaşanan

bir olay kanıtlıyordu. Bu tarihte

eşkıyalar buz taşımakta

olan buzcuları Gemlik Katırlı

Dağları’nda rehin almış ve

saraya “eğer istediğimiz parayı

vermezseniz, dağlardan buz

ve kar alamazsınız” diye tehdit

etmişlerdi. Yaşanan bu sıkıntı

kar ve buzun değerini daha

da arttırmıştı çünkü yazın

sıcağında bozulup kokuşan

yiyecek ve içeceklerin hepsi

ziyan olmuştu.

Buzculuk yalnızca sarayın ve

halkın ihtiyacını karşılamakla

kalmıyor, Osmanlı’nın en

önemli ticaret merkezlerinden

biri olan Bursa’nın ticari

açıdan gelişmesine de katkı

sağlıyordu. Mesleğin etkin

olduğu dönemlerde İstanbul’a

ya da Bursa’ya gelen yerli

yabancı seyyahlar, yazarlar

bu ticareti gözlemleyerek,

yalnızca bu işi yaparak

büyük ticari kazançlar elde

edildiğini aktarıyorlardı.

Özellikle Müslümanlar

food and drinks that went bad in

the heat of the summer months

had to be thrown away.

Icemen not only met the

demands of the palace and the

public, but also contributed to

the commercial development

of Bursa which was one of the

important trade centers of the

Ottoman Empire. Local and

foreign travelers as well as writers

who came to Istanbul or Bursa

at the time when this occupation

was at its peak observed this

trade and stated afterwards that

high profits could be acquired

by only doing this job. Uludağ

was believed to be almighty and

miraculous especially by the

Muslims and ice wells were dug

up at the region known today as

the snow pit; the snow acquired

from here was accepted as the

property of the Ottoman sultans

and could be rented. Snow

commerce provided a significant

contribution to the treasury

and the snow was carried via

the western path to Kadıyayla

on mules some of which were

handed over to the palace while

the remainder was sold to the

public. The icemen who took

off towards Uludağ every day at

about 5 p.m. came back to Bursa

at 9 a.m. in the morning. The

workers who toiled without any

rest covered the ice in special

felts so that they would not be

damaged on the way, whereas

ice was cut only during June 15 –

August 15 when it was the most

suitable time to do so. Their route

started from the Hünkâr Palace,

passed by the Buzcular Fountain

and reached the mountain via

Yantekir, Sarıalan, Dombay Pit.

After snow was collected from

the Dombay Pit they reached

the dairy but snow collection

continued at the Küçükkuyu,

Büyükkuyu regions. Gölbaşı

was the last spot where ice

that could be cut only by axes

was collected. This took about

11 hours. The region known

today as “karlık” was once

the workplace of icemen that

worked continuously to serve

the public. Their occupation

took its place amidst the dusty

pages of history, but the traces

of their service that continued

for centuries still remain. Their

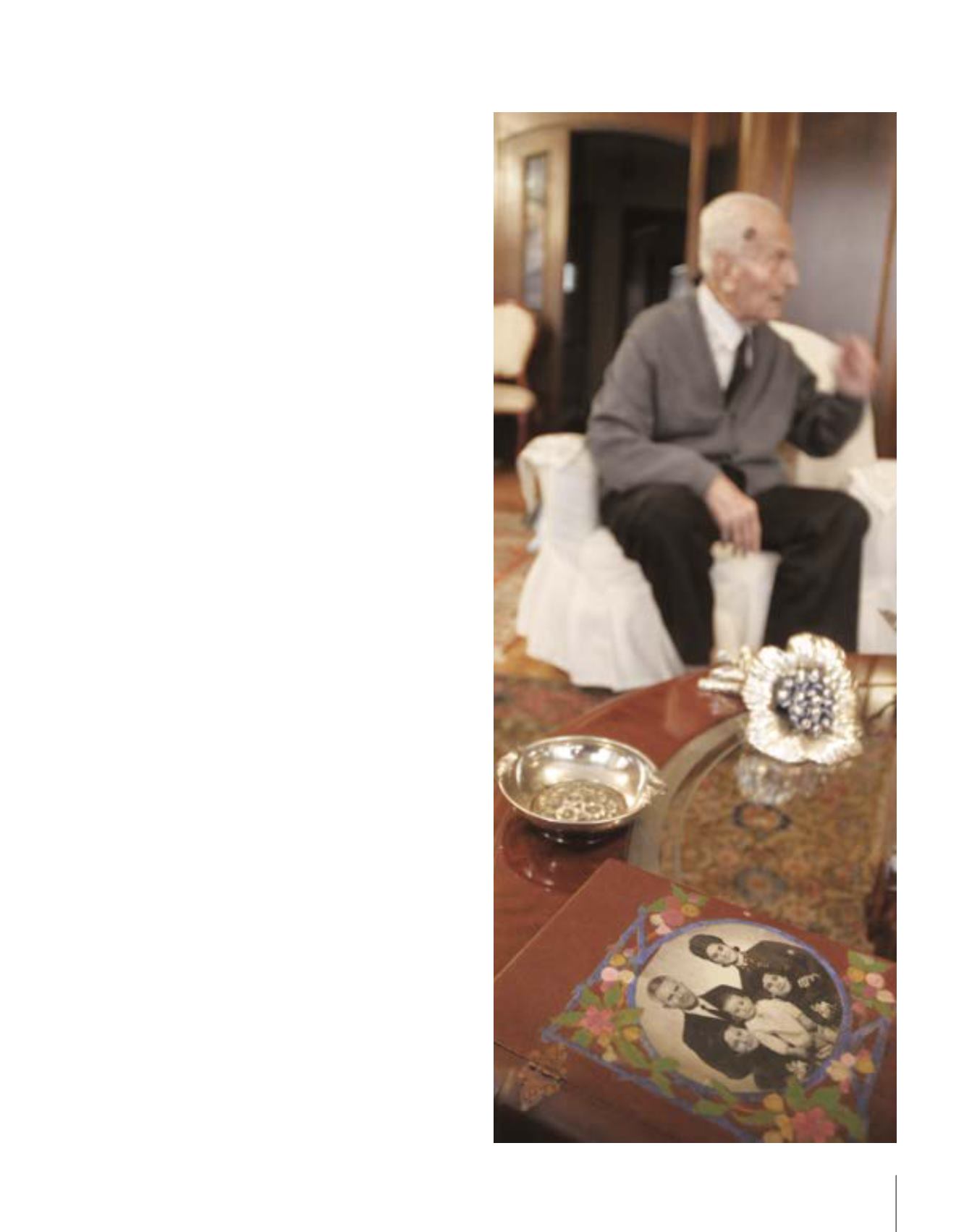

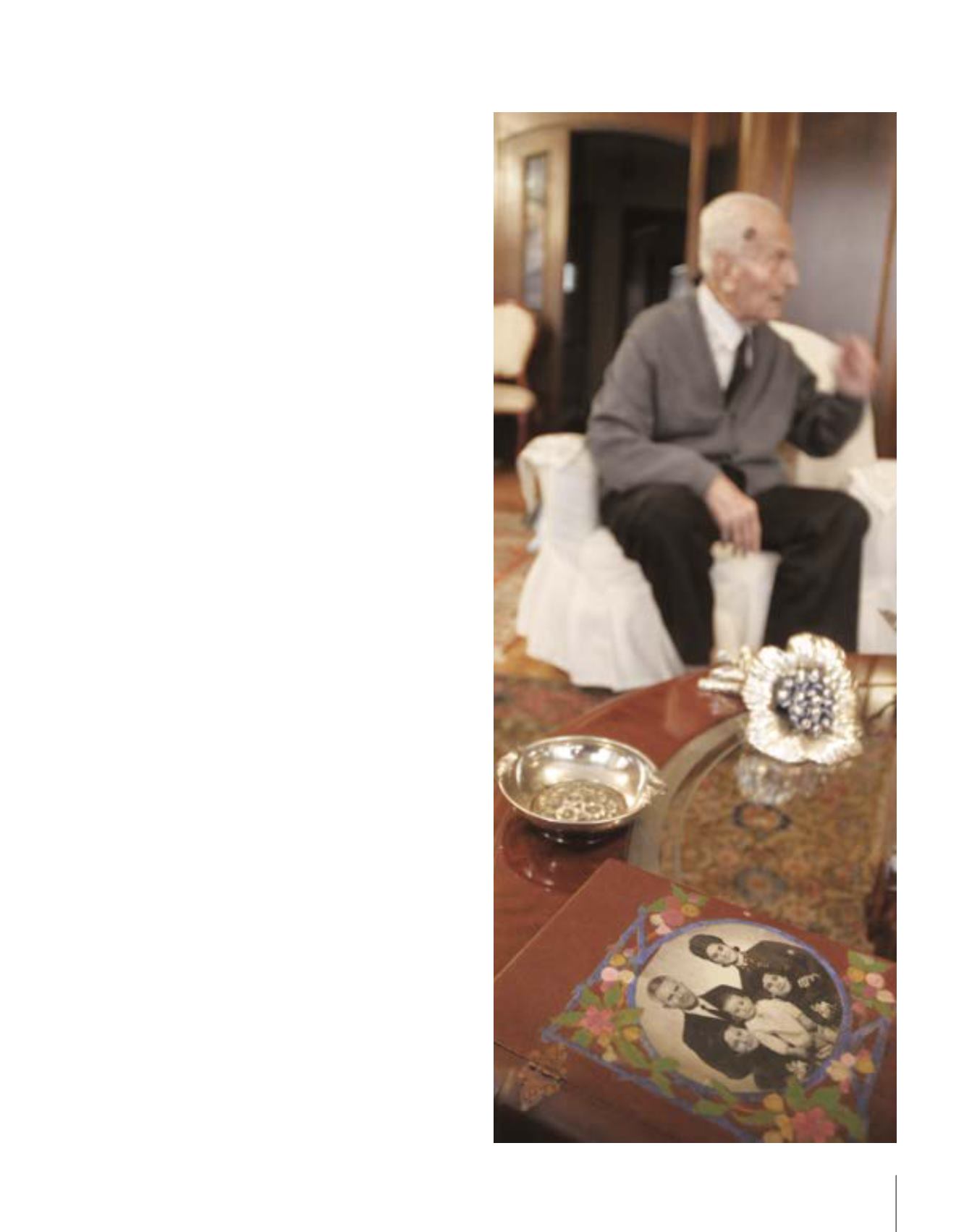

grandson Ismail Buzcular who

sought these remains took it onto

himself to serve Bursa all his life